Jacksons Landing

1788

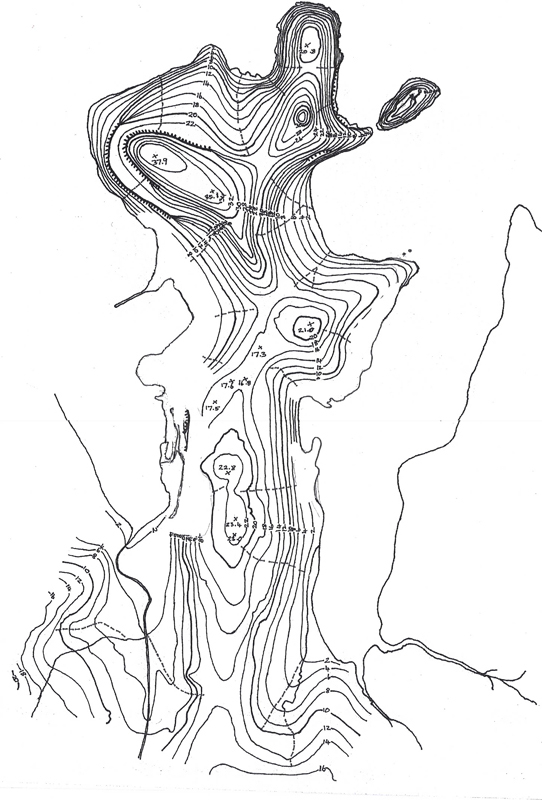

Two centuries of tree-felling, quarrying, manufacturing and residential development make it difficult to imagine the peninsula when the First Fleet arrived. The land was much higher, especially its Northwestern corner: McCafferys Hill is one of few remaining high points in the landscape.

Vegetation was transformed, and the animals and birds that lived here. Early colonists, expecting wilderness like Africa or the Americas, were surprised by an environment resembling the parks that were landscaped for English landowners. Hunter, in 1790, walked through pleasant country

which, from the distance the trees grew from each other, and the gentle hills and dales, and rising slopes covered with grass, appeared like a vast park.

John Macarthur’s visitors made a similar point in 1806, when the land reminded them of Bad Pyrmont, a quiet German spa town.

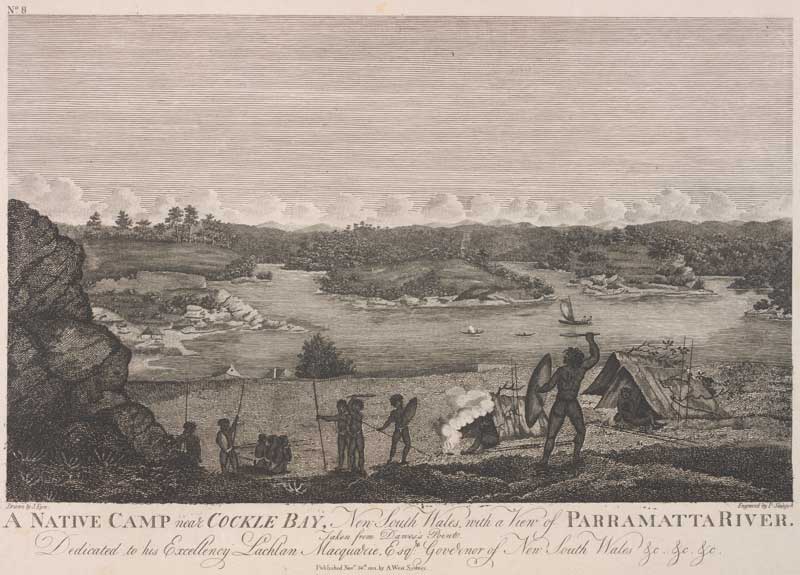

These features were the result of Aboriginal fire-stick farming, which maintained grazing land for animals, and clumps of trees from which hunters speared them. Around Sydney Harbour, clans of the Eora nation were well nourished by a varied diet: mangroves supported ample shellfish (including cockles in Cockle Bay and Balmain bugs); there were fish to spear and eels to trap. The clans were almost wiped out by smallpox in 1789, and very few remained in this vicinity. Their successors began to transform the environment.

Surgeon John Harris seized the opportunity to acquire most of the peninsula, and build an English country house, turning much of his Ultimo land grant into a deer park. The Harris family did, however, allow masons to quarry stone at the northern tip of the peninsula, which they sold as ballast. John Macarthur’s Pyrmont land grant, smaller and closer to the city, changed much sooner: trees were felled, businesses established and houses built.